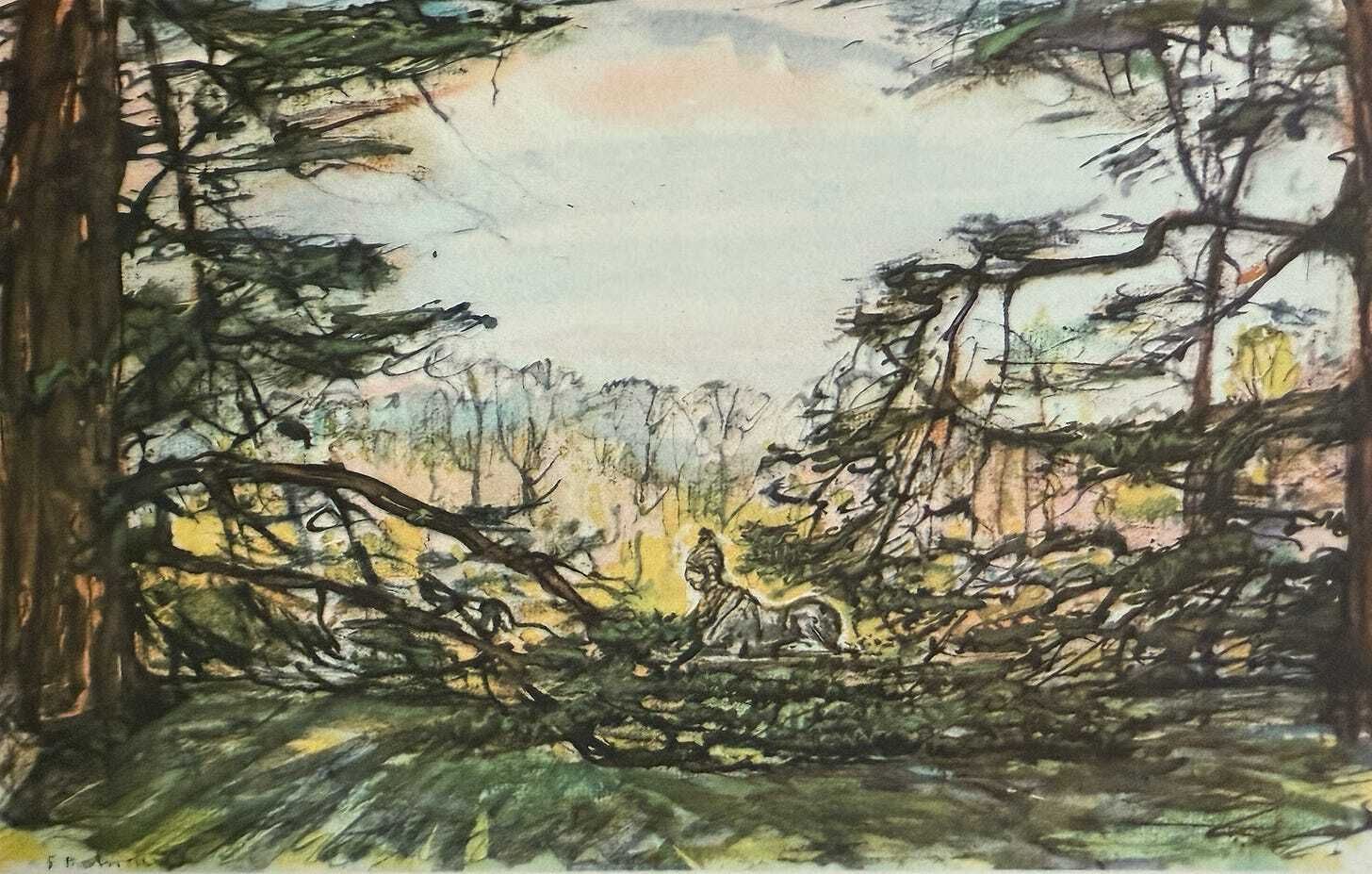

A.S. Hartrick, Chiswick House, The Cedars And The Sphinx, c1940. V&A Museum, London.

The beautiful park, 66 acres in extent, surrounding Chiswick House was laid out by William Kent1 in 1730; developed some fifty years later by Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire;2 adapted to suit the zoological leanings of the 6th Duke;3 and since 1939 further modified, temporarily if not lastingly, by the lorries of the National Effort.4

Avenues, glades, lake, bridge, cypresses, cedars, yews, vistas, temples, statues, urns, hermitages, and grots – all are, or were, dutifully and delightfully included. Some of these features were later removed to Chatsworth.5 Others – even Walpole thought there were rather too many of them – have simply vanished.

The 6th Duke, last of the three Dukes of Devonshire to inhabit the house, kept a menagerie. Amid the Ionic temples and the classic statues, kangaroos, deer, elks, emus, ‘and other pretty, sportive death-dealers’6 were to be met, or avoided. An Indian bull and his mate and goats of all colours and dimensions ‘beautifully variegated’ the lawn. Walter Scott, wandering through the grounds in 1828, encountered a female elephant and remarked on its size.7 The Duke’s sister, Lady Granville, some of whose appreciative comments have already been quoted, declared that her brother ‘had opened and aired’ the place. He left her the property.

From beneath the boughs of the cedars of Lebanon which line the main road to the house, and beyond it, Kent’s sphinxes gaze across a valley in which a stream has been dammed to form a lake. Elsewhere, three avenues of yew, 160 yards long, used to converge upon a group of buildings. Only one remains. It is known as Napoleon’s Walk because, though it must have been planted before Bonaparte had been heard of or, perhaps, born, the trees hold an alcove in which a bust of the Emperor formerly reposed.8 Mr. Hartrick reported that, when engaged on his water-colour, he came across ‘a small temple at the corner of a dung-heap, fenced in with small-meshed wire like a chicken house. Within a carefully spaced and studied recess stood a gilded bust, a good one, of the great Napoleon, in plaster beginning to peel – and round about it on the ground all the debris of a potting shed – pea stakes, brushwood and what not, together with a medley of forgotten wrappings.’9

Recording Britain, Vol 1, London and Middlesex, p 56-57.

Image: A. S. Hartrick

Text: Arnold Nottage Palmer

1 William Kent (1685-1748), English architect, landscape architect, painter and furniture designer.

2 Yes, that Duchess of Devonshire – Georgiana Cavendish, famed 18th-century socialite, fashion icon, and all-round renaissance woman.

3 He even had a banana named after him.

4 The house was sold to Middlesex County Council in 1929, then handed to the Ministry of Works in 1948. It was transferred to English Heritage in 1984. Finally, the Chiswick House and Gardens Trust was formed in 2005, integrating the management of the house and gardens.

5 The Cavendish Family owned Chatsworth in Derbyshire as well.

6 A letter from the Duke’s sister Harriet (Lady Granville) wrote to their sister Georgiana, October 1820: “He [the Duke] is improving Chiswick most amazingly, opening and airing it and a delightful walk is made around the paddock, open and dry, with a view of Kew Palace – and a few kangaroos (who if affronted rip up a body as soon as look at him), elks, emus and other pretty sportive death-dealers playing around near it.”

7 The reference is to Scott’s journal, dated 17 May, 1828: “A numerous and gay party were assembled to walk and enjoy the beauties of that Palladian [dome?]; the place and highly ornamented gardens belonging to it resemble a picture of Watteau. There is some affectation in the picture, but in the ensemble the original looked very well. The Duke of Devonshire received every one with the best possible manners. The scene was dignified by the presence of an immense elephant, who, under charge of a groom, wandered up and down, giving an air of Asiatic pageantry to the entertainment. I was never before sensible of the dignity which largeness of size and freedom of movement give to this otherwise very ugly animal. As I was to dine at Holland House, I did not partake in the magnificent repast which was offered to us, and took myself off about five o’clock.” This was just four years before Scott’s death in 1832.

8 Another Emperor, Tsar Nicholas I, was the honoured guest of a grand banquet hosted by the 6th Duke here on 8 June 1844.

9 At the time of Hartrick’s visit, the house and grounds had fallen into some disrepair. A few years later, in 1944, anticipating the fears of the Recording Britain project, a V2 bomb reportedly hit one of the 18th-century wings, an event recorded in John Richardson’s The annals of London : a year-by-year record of a thousand years of history (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000): “Just as the RAF was getting to grips with the flying bombs the V2 rocket arrived. This was a 45-ft-long ballistic missile, travelling too fast to engage; the first one fell on Chiswick on 8 September.” The wings were finally removed in 1956.