St. Peter’s Church, Theberton, Suffolk. Image: Ben Murray

Readers will be relieved to learn that the stunning parish church in the Suffolk village of Theberton remains exactly as it was sketched by Jack L. Airy for Recording Britain in the early 1940s. A quick comparison shows just how durable it is. Sempiternal even.

Jack L. Airy, St. Peter’s, Theberton, c 1940. V&A Museum, London.

Notice some of the less obvious features of his picture. The small circle and star either side of the window beneath the tower for instance. Seeing the real thing made sense of these. The whole church is adorned with symbols like this – a feature known as flushwork, which is prevalent on churches throughout East Anglia.1

These striking adornments are made from a combination of limestone ashlar and knapped flint. Many carry heraldic, patronal, or pre-Reformation theological symbolic meanings.2 The star typically signifies the divine light of Christ. This kind of adornment reached its apotheosis between 1450-1520, during the ‘wool boom’, when affluent merchants funded the construction of numerous churches across the region.3

The intricacy of its external ornamentation lend the building a strange, almost otherworldly quality. I can imagine Alan Garner having a field day with this place. The earliest parts date back to the 12th century. Additional features were built and restoration work carried out in the 14th, 15th and 19th centuries.4 The thatched roof is still in place, last re-thatched in 1973.

The tower is particularly imposing from the ground. The octagonal belfry which crowns it was added in 1300. When we visited, a lone campanologist was giving it some welly up there, the bells reverberating across the churchyard, a thinner, more metallic sound than I’ve heard before, adding to the unearthly atmosphere.

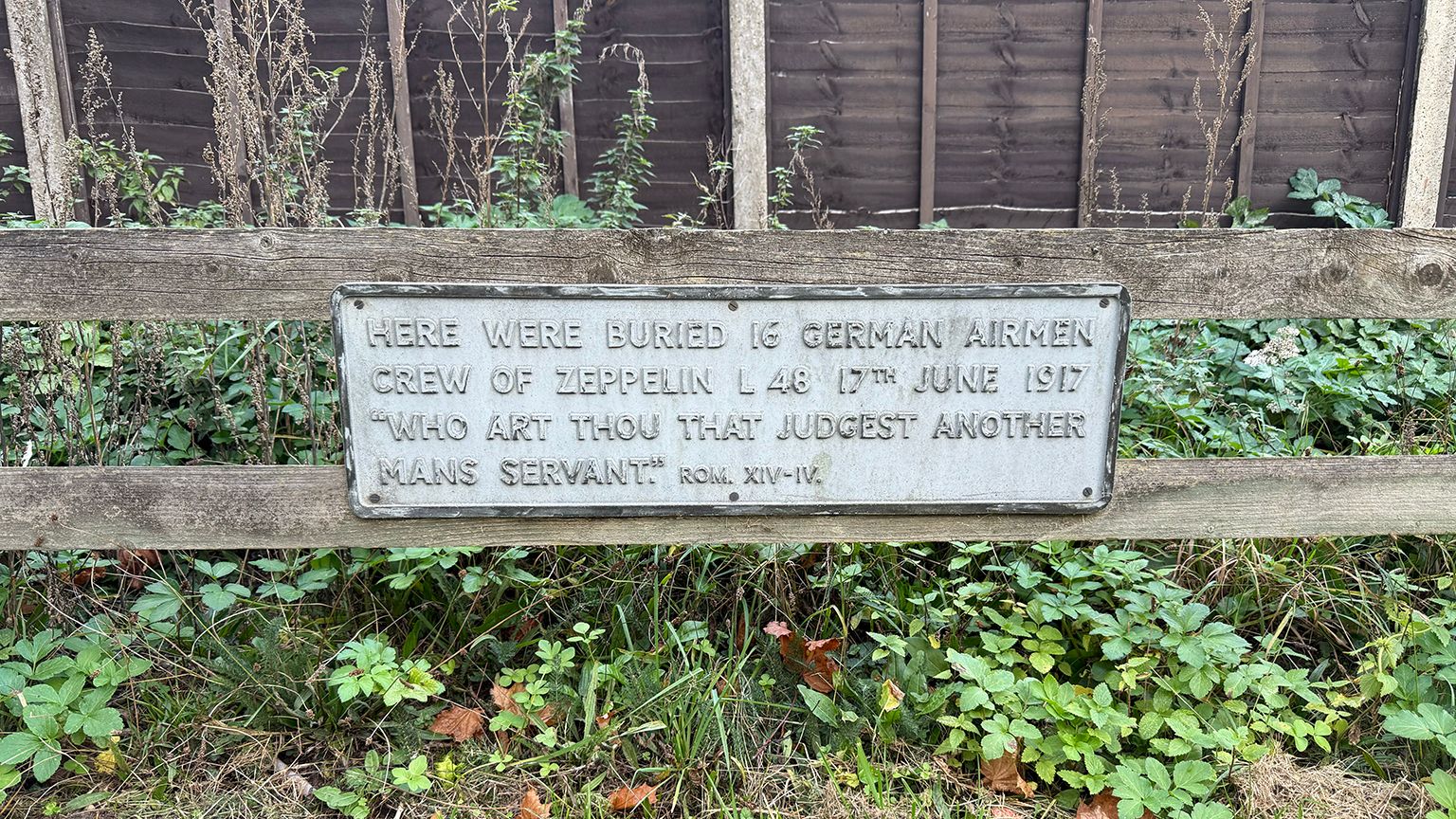

This superlunary vibe is only heightened when one considers the wartime legacy of this place, which is marked in the church, and carries beyond the village to this day. Theberton was famously the location of the last German zeppelin to be shot down over England in WWI. The bodies of 16 crew members were initially buried here, before being transferred 40 years later to a military graveyard in Staffordshire. Crossing the road into an extension of the graveyard, we found a commemoration to the dead.

I return to East Anglia again and again. It has something deep and wide about it. Big skies. Ethereal light. I spent four years living here many moons ago, and, since leaving, have long enjoyed dreaming and reading about this part of England. The ghost stories of M.R. James spring to mind. And Rings of Saturn by W.G. Sebald. East Anglia is an edge land. It speaks to our sense of mystery, I think, to that psychogenic pendulum that leads us backwards, forwards, and even into die jenseitige Welt.

1 For more on the fascinating history of flushwork see Stephen Hart’s Flint Flushwork: A Medieval Masonry Art (The Boydell Press, 2008).

2 For those looking to go even deeper, try John Blatchly and Peter Northeast’s Decoding Flint Flushwork on Suffolk and Norfolk Churches : A Survey of More Than 90 Churches in the Two Counties Where Devices and Descriptions Challenge Interpretation (Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History, 2005).

3 These are known as the ‘Wool Churches’.

4 During the 1846 restoration the south aisle was rebuilt by Rev. Charles Montagu Doughty of Theberton Hall. His son was the well-known writer, traveller and orientalist, C.M. Doughty, beloved by T.E. Lawrence, bemoaned by E.W. Said.